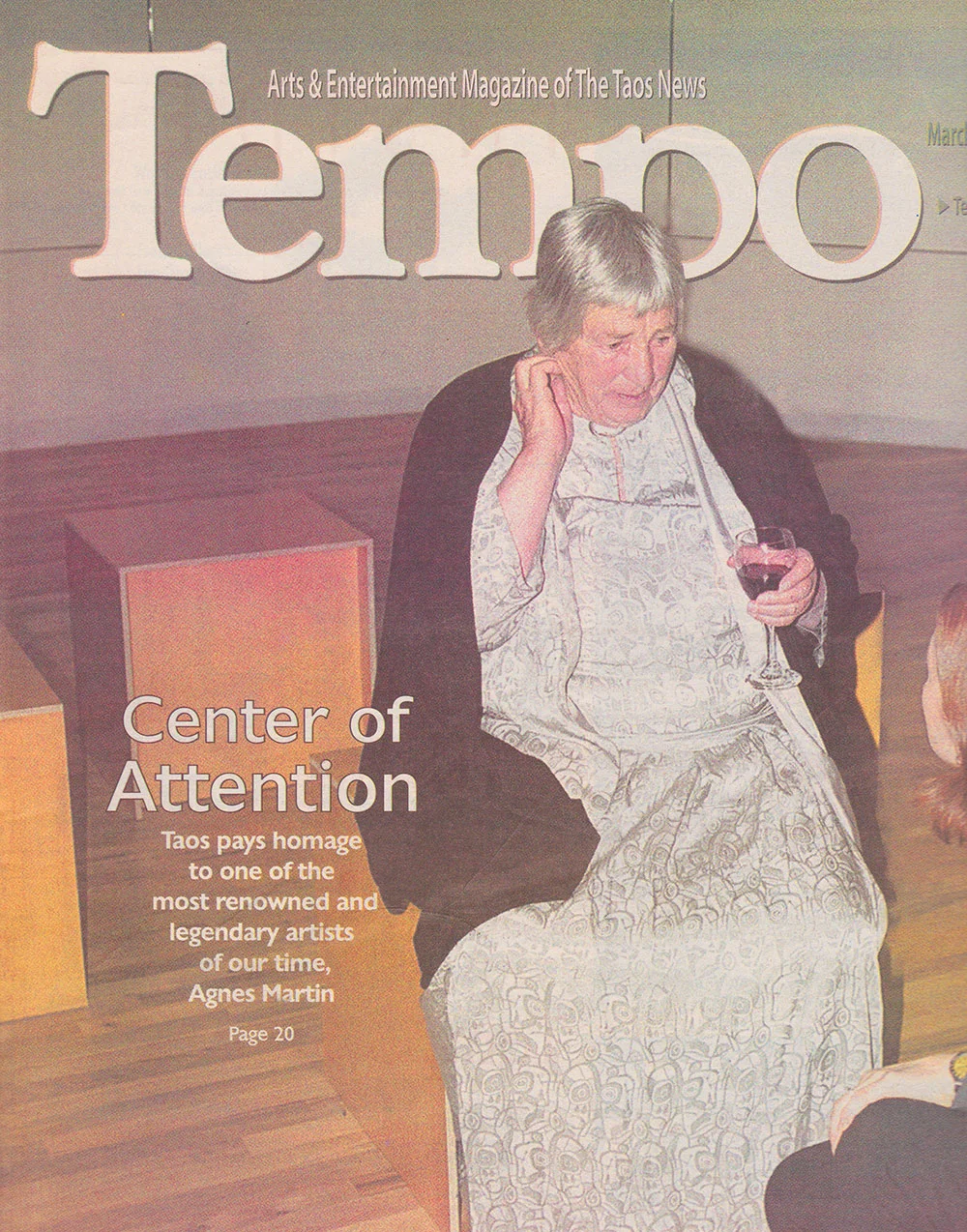

CENTER OF ATTENTION

Tempo Magazine Cover Story, The Taos News, 2002

By Denise Spranger

“One day, Agnes Martin wandered alone upon a 1,000-foot-high mesa in New Mexico. A light snow had fallen. Finding footprints between the whitened sagebrush, she mourned the loss of her solitude. In the next moment, Martin realized that she had walked in a circle.

The footprints were her own.”

As the University of New Mexico's Harwood Museum of Art celebrates the 90th birthday of Agnes Martin with an exhibition and weekend symposium Friday through Sunday (March 22-24), we honor the broader circle of Martin's life.

Born March 22, 1912, Martin, a native of Maklin, Saskatchewan, Canada, moved to the United States in 1931, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1950. After attending Western Washington College of Education in Bellingham, Wash., and Columbia University in New York City, Martin enrolled at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where she also taught art from 1947 to 1948.

Harwood Museum curator and author David Witt ("The Taos Moderns") describes how Martin first came to Taos.

"In the summer of 1947, Agnes was attending the UNM Summer Field School of Art, which happened to be in Taos and was headquartered at the Harwood," said Witt. "That summer there was an exhibition of all the students attending the Field School, which was held at the Harwood."

An article printed in El Crepusculo (precursor to The Taos News) referred to both Martin and Earl Stroh as "two of the more advanced students in the exhibition."

"We believe that the first time Agnes showed her work in a museum was at the Harwood," said Witt, "and Agnes has never refuted this."

In her relationship with the Harwood Museum and Taos, the circle now encompasses more than half of a century.

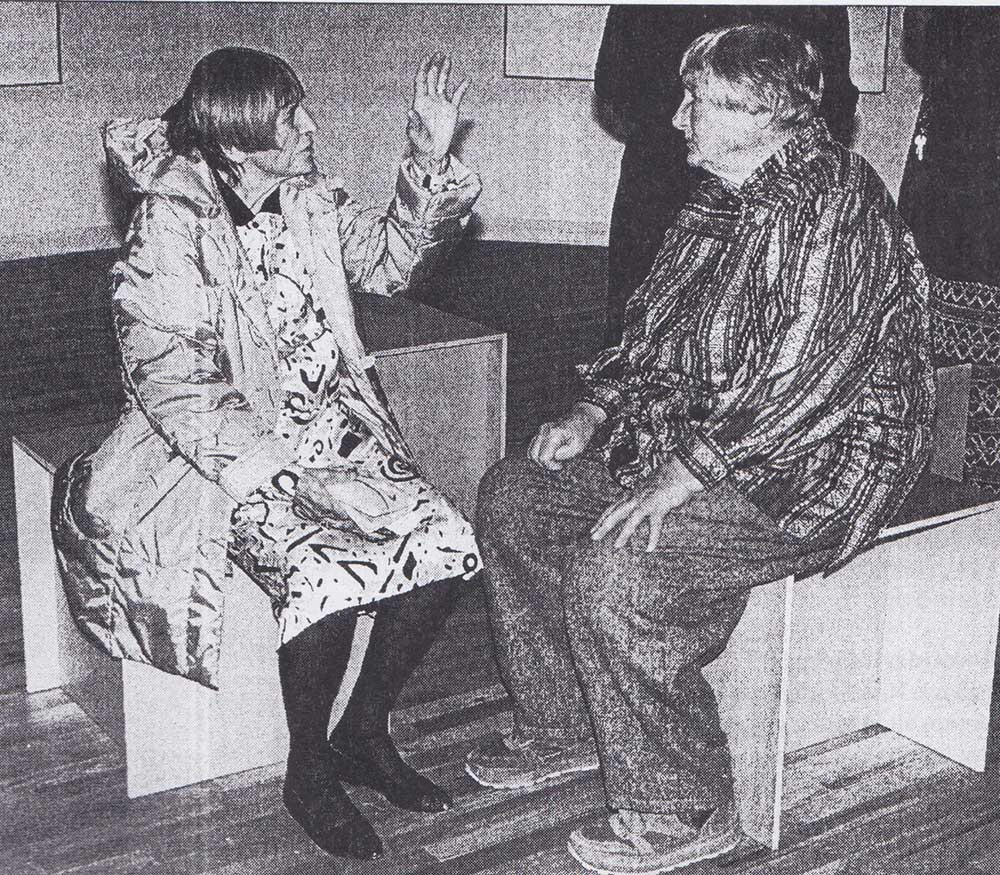

A CONVERSATION WITH AGNES MARTIN

At her home in a local retirement community, Martin spoke about her life, her philosophy of love, and why she refuses to discuss her art. She also explained her decision to move to Taos in 1954, which refreshingly had nothing to do with the "quality of light."

"I came to Taos because New Mexico was the second poorest state in the union and I expected prices to be low," said Martin. "But I didn't expect them to be that low."

Martin lived and painted in a studio space next to the Harwood Museum. Her rent was $15 per month.

"I realized that I came to the right place," said Martin, "I thought it was a wonderful town, a wonderful place to be."

It was some time, however, before the artist, who still paints daily, became satisfied with her work.

"I painted for 20 years but I didn't like my paintings," she said, "so I didn't show or sell them. I used to burn them at the end of every year."

Fortunately, some of those paintings escaped the flames. In 1957, Martin was invited to show her work in the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, where she held her first solo exhibition in 1958. Living and painting in an old sailmaker's loft in lower Manhattan, Martin's work gained serious recognition. In the 1960s, she was invited to show with a group of Minimalists who had begun to establish a new-found prominence on the New York art scene.

"The Minimalists were a bunch of young men who claimed that they were influenced by me," said Martin. "I don't believe in influence, but I thought I would show with them just for fun."

"Ever since, I've been called a Minimalist," noted Martin. "But I'm not, you see, because the Minimalists didn't believe in any personal feelings. You're not supposed to get emotional about minimalist painting.

"I consider that there is emotion in my work and I expect an emotional response," Martin continued. "That makes me an abstract expressionist."

Martin recalled an amusing anecdote from the time that still makes her smile. A woman interested in promoting Minimalist work invited the group to discuss the production of a catalog.

"These young boys came to the meeting, but they didn't want a catalog," said Martin. "They didn't want to be called 'American Painters.' They didn't want anything personal or their persons to be connected with paintings. It was kind of hard to figure. But the woman served them such good liquor," added Martin, "that they decided to stay around."

Along with her work itself, Martin's iconoclasm is also expressed by her nonparticipation in the ongoing analysis of art.

"We have five magazines a month talking about art, and really, there's nothing to say," said Martin.

"Painting isn't intellectual, it's emotional," added Martin, "Yet everybody writes about art as if it were intellectual, as if it were about ideas. But it isn't about ideas at all. Our response to ideas is more ideas, right? That's not our response to art."

While some are willing to give a grudging respect to Martin's stance, many more remain mystified by an artist who has no interest in an increasingly verbal art world.

"I don't know how to get this across, that you're not supposed to think about art," said Martin. "Just let it speak to you."

Just as Martin resists the intellectual response to art, she maintains that neither is the intellect its source.

"It's not about brains. Inspiration is about sitting and waiting," said Martin. "You don't use intelligence when it comes to making things, it wouldn't get you anywhere."

Road trip

In 1967, Martin's life abruptly changed. Receiving notification that her loft in New York City was soon to fall under the demolition ball of urban renewal, the painter simply walked away.

"The very day that I heard they were going to tear down my loft, I also got a letter that gave me a $5,000 award for painting," said Martin.

After taking a bus to Detroit, the fleeing artist headed for a Dodge dealership.

"I picked out the liveliest salesman and said, 'Here's a check for $5,000, what kind of truck can hold a camper?'"

Rolling out of the Motor City in the largest camper-truck that the dealer carried, Martin turned the wheel to the north.

"I went all over," Martin said. "I drove 6,000 miles in northern Canada alone. I spent almost two years driving around and wondering where to go. I slept in the back of the truck."

Perhaps even more intriguing than Martin's "walkabout" was the fact that it heralded a lengthy estrangement from a life-long commitment. For seven years, Martin didn't paint.

Her explanation is no less surprising than her journey.

"I was selling out my shows and I was right on 'top of the heap,'" said Martin, "But I thought the younger ones were anxious to walk over me and I thought I'd let them do it. I thought, 'They can have it.'"

Martin's wanderings finally took her to New Mexico, where as Witt said, "She disappeared into the wilds above Cuba." It was here that Martin lived on the 1,000-foot-high mesa, building her home and spending much time in solitude.

"It was all one big long meditation," said Martin, "I don't get lonesome and I don't get afraid. That's what you have to be to live on the mesa."

Martin rejoined the world of working artists in 1974, partly in response to the artists she had left to fill her shoes.

"I wasn't satisfied with what they did so I had to start again," she said.

The capacity for change is essential to the artist who feels that "art evolves with us."

"I used to pay attention to the clouds in the sky," said Martin, "I paid close attention for a month to see if they ever repeated. They don't repeat. And I don't think life does either. It's continually various. That's the truth about life."

Protest film

In 1976, Martin produced her first film, "Gabriel," a 90-minute feature that will be shown as part of the Harwood Museum event.

"I made it in protest against the commercial movies that are all about destruction and deceit," said Martin, "I thought I'd make a movie about happiness and innocence and see if anybody came."

The theme of the film echoes in Martin's life and work.

"I don't paint the darker side. I stay above the line. Above the line is love and happiness. Below the line is everything depressive, everything destructive and wrong," said Martin. "I paint above the line and I live above the line."

Living above that line reflects one of Martin's deepest beliefs.

"I believe that love still fills the world and it's all around us like air," she said. "It's pressing in on us, pressing love on us. That's what makes us want to love as love does."

The artist spoke about the kind of love she embraces.

"It is not intense," she said, "I've given up the passions. It's like how the babies laugh, and the little children too. They are only love – that is why they very generously give it to whoever comes near them. That is the love that I paint about."

Being alone

Martin's choice to live alone has prompted questions about her sense of fulfillment.

"When people ask me if I'm not disappointed because I didn't get married and don't have children, I tell them I believe in reincarnation," said Martin. "I've been married a hundred times and I've had hundreds of children. This time I asked to be left alone."

Still living alone in her 90th year, Martin retains her dedication to independence.

"You give up your life if you attach yourself to somebody or something," she said. "That's a very great danger. You have to prize your life above everything else."

Though Martin would undoubtedly say that the same was true for any life, her own has certainly been one to prize.

In the years following her re-emergence, Martin achieved international stature as one of the world's leading abstract painters. Yet even as Martin enjoyed such worldwide acclaim, her ties with the Harwood Museum were not forgotten.

Researching his book "Taos Moderns: Art of the New," Witt renewed contact with Martin, then living in Galisteo, in 1986. After moving to Taos in 1992, Martin soon developed a friendship with former Harwood Museum director Bob Ellis.

Following Martin's 1994 exhibition at the Harwood, the artist donated the group of seven paintings to the museum. Upon completion of its major renovation and expansion project in 1997, the Hardwood Museum now contains a permanent exhibition of the artist's work in the octagonal-shaped space of The Agnes Martin Gallery.

"People have come from all over Europe and the United States just to see that one gallery," said Witt.

Thirty four-year-old New Zealand artist Valerie Nielsen Quintana said that she first came to Taos to see Martin's work in the Harwood.

"The fact that there was a woman out there doing that work really inspired me," said the recipient of a Creative Grant sponsored by the New Zealand Arts Council.

Cause for celebration

This weekend's celebration will include a dinner noting the artist's 90th birthday; a symposium in which five scholars plan to present their papers on Martin's work; an exhibition of 10 new works painted in Martin's Taos studio in 2001; a live performance by the Taos Chamber Music Group; and a screening of "Gabriel."

"This event has been over five decades in the making," said Witt. "Given the Harwood's long relationship with Agnes as a supporter of her work, we felt we were the right ones to offer this kind of special recognition."

Harwood Museum director Charles Lovell reported that as of March 12, more than 200 people from 13 states and Canada had already signed up for the symposium.

"It's really a momentous event in Taos," said Lovell, "Agnes is a living national treasure."

As a community joins to celebrate the life of one of its most beloved artists, Martin remains a woman who is content to find in the path she cleared no footprints but her own.

"Life is a tempering of the ego," said Martin. "I hope I've shed it. All I have to think about now is painting, so I've painted better and more, even though I'm old. I'm happier and more at peace than I've ever been."

Agnes Martin biography:

Born March 22, 1912 in Maklin, Saskatchewan, Canada.

1934-37 attended Western Washington College of Education, Bellingham.

1941-42 attended Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, receives bachelor of science degree.

1946-48 teaches art at University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

1947 UNM Summer Field School of Art, exhibits at Harwood Museum, Taos.

1952 receives master's degree Teachers College, Columbia University.

1958 first solo exhibition, Betty Parsons Gallery, New York.

1975 begins association with the Pace Gallery, New York.

1989 inducted as member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York.

1991 retrospective exhibition organized by the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; receives the Alexej von Jawlensky Prize from the city of Wiesbaden, Germany.

1992 receives Oskar Kokoschka Prize from the Austrian government.

1992-94 retrospective organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

1997 receives the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale in recognition of her lifetime achievement of 60 years of painting and her contribution to contemporary art.

2002 Agnes Martin: The Nineties and Beyond, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas.

2002 Agnes Martin Symposium and exhibition, "Paintings from 2001," Harwood Museum, Taos.

Photos: Rick Romancito for The Taos News